How did we make this edition?

Planning a variorum reading experience

This is a variorum edition in the sense that it assembles and displays the variant forms of a work. In designing this Frankenstein Variorum, we are grateful for inspiration and consultation of Barbara Bordalejo and her Online Variorum of Darwin’s Origin of Species, which shared a similar goal to represent six variant editions published in the author’s lifetime over a period of 14 or 15 years. We were also impressed with Ben Fry’s “On the Origin of Species: The Preservation of Favoured Traces”, an interactive visualization of how much that work changed over 14 years of Darwin’s revisions, where on mouseover, you can access passages of the text in transition. In our team’s early meetings at the Carnegie Mellon University Library, we sketched several design ideas on whiteboards, and arrived at a significant decision about planning an interface to invite reading for variation. Side-by-side panels are typically how we read variant texts (via Juxta Commons, which was then popular, or the Versioning Machine, or the early experiments with the Pennsylvania Electronic Edition’s side-by-side view of 1818 and 1831 Frankenstein texts).

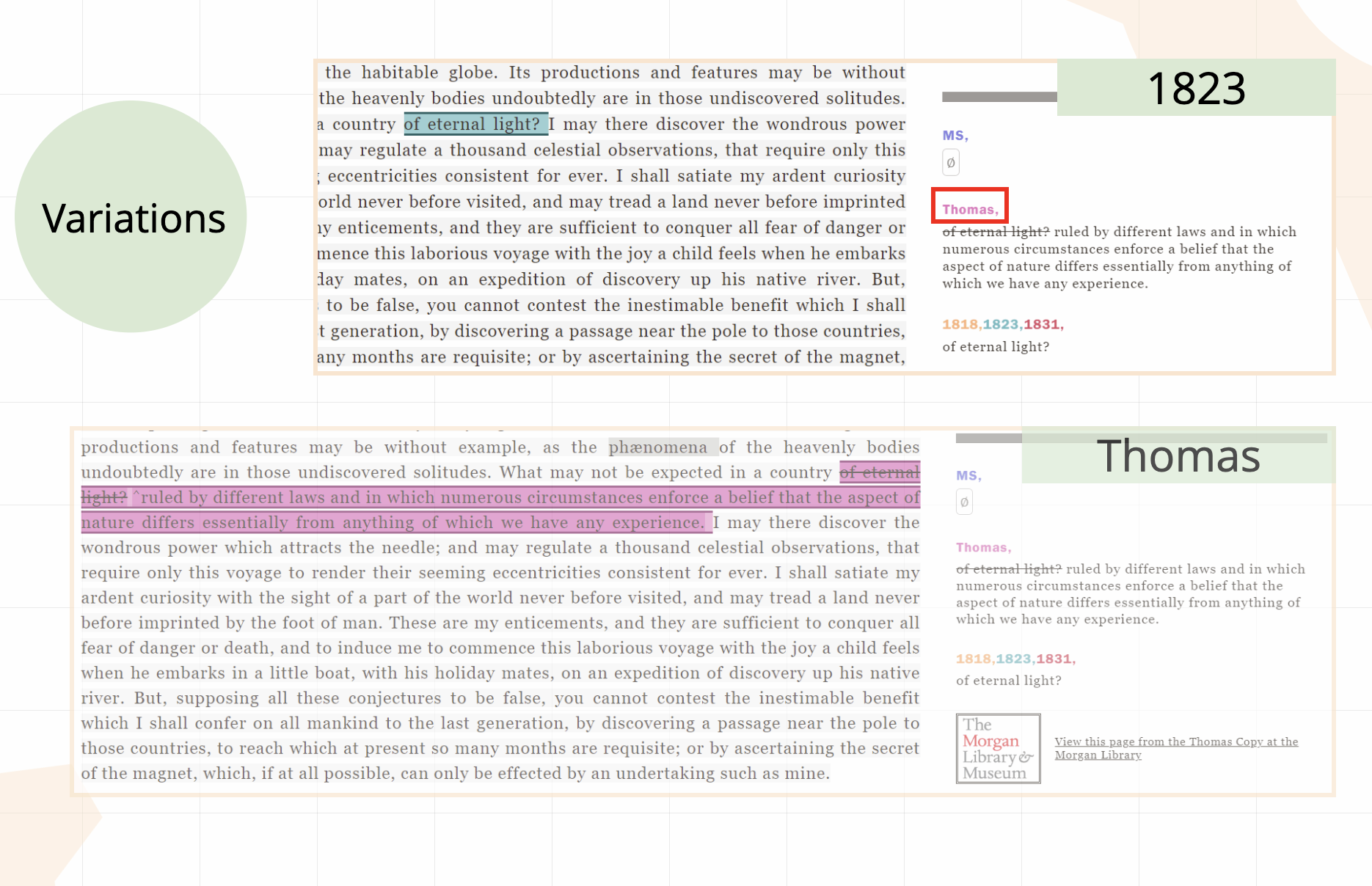

We agreed that surely a five-way comparison was not best served by five narrow side-by-side panels, yet we wanted our readers to be able to see all available variations of a passage at once. For this a note panel seemed most appropriate, especially if we could link to each other edition at a particular instance of variation. Bordalejo’s Variorum highlights variant passages color-coded to their specific edition and offers a mechanism to view each of the other variants on that passage—momentarily on mouseover of the highlighted text. We admired this ability to see the other passages, but we also wanted it to be more available to the viewer and saw it as a basis for navigating and for exploring the edition across its versions. Our Variorum viewer is related to that of the Darwin Variorum, but we decided to foreground the variant apparatus view and make it the basis of visualizing and navigating our edition.

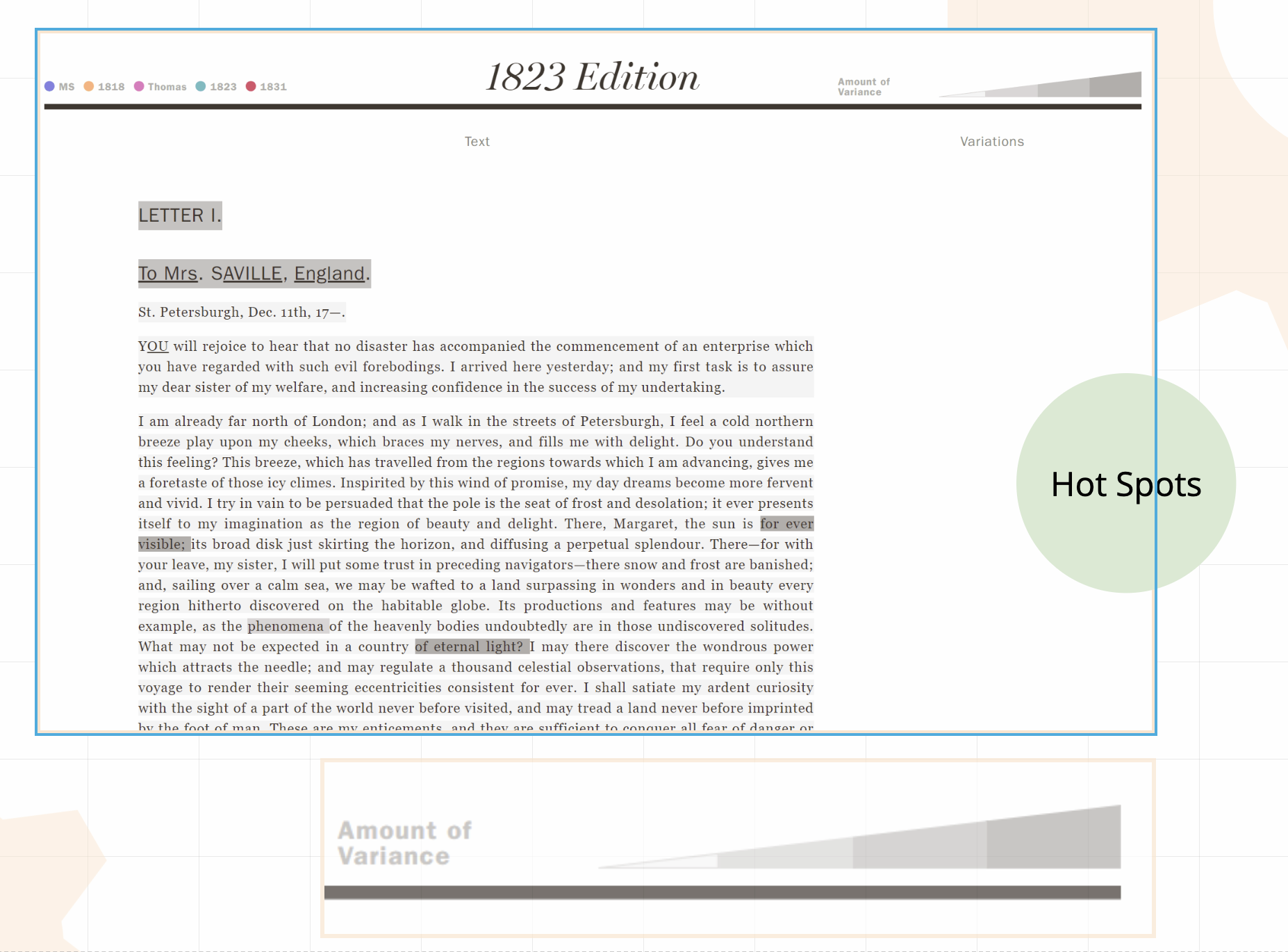

We also decided to display just one edition in “full view” at a time and to foreground its “hotspots” of variance, to alert the reader to passages that are different in this text than in the other versions. As they explore a particular edition, readers can discover variant passages based on highlights of light to dark intensity.

When you interact with a variant passage in the Frankenstein Variorum Viewer, a side panel appears to display the data about variation in each of the other four editions. The information displayed in this side panel is known as the critical apparatus, which is designed in scholarly editions to store information about variation. That side panel not only displays variants but also directly links the reader to each of the other editions available at that moment. So, instead of displaying all five editions side by side, we chose to foreground a “wide angle” view of all variations at once in our critical apparatus panel, and make that panel a basis for navigation to see what each of the other editions look like at a moment of variance.

Note that the critical apparatus panel displays the variant passages differently from a passage’s literal appearance in its source text (visible on click). This is because our critical apparatus view displays normalized text showing our basis for comparing the editions. For example, the normalized view ignores case differences in lettering, interprets “&” as equivalent to “and” and signals where some versions hold paragraph or other structural boundaries and others do not. To view the text as it distinctly appears in its source edition, follow the link to it in the critical apparatus panel. In openly sharing the normalized view of the texts in the critical apparatus panel, we are featuring not only the variations but also our basis for identifying and grouping those variations.

While the Frankenstein Variorum may certainly be accessed to read a single edition from start to finish, it seems likely that readers will wish to go wandering to explore the edition at interesting moments, collecting digital “core samples” of significantly altered passages to track their changes. We recommend reading the Frankenstein Variorum from any point of departure and in any direction. We invite the reader to a non-linear adventure in reading across the editions and exploring for variation. Exploring variants in this edition may complement reading a print edition of Frankenstein, and we hope that combining the reading of multiple texts will reward curious readers, student projects, and scholarly researchers investigating how this novel transformed from 1816 to 1831.

To accomplish the vision of our interface, we had much work to do to prepare the texts for comparison. What follows is a brief, illustrated explanation of how we prepared this project.

Preparing the texts for machine-assisted collation

When we began this project, we set ourselves the challenge to collate existing digital editions of the 1818 and 1831 texts with the Shelley-Godwin Archive’s TEI XML edition of the manuscript notebooks (the S-GA “MS” in our Variorum). The print editions were encoded based on their nested semantic structure of volumes, chapters, paragraphs, with pagination in the original source texts a secondary phenomenon barely worth representing on the screen. The S-GA’s preparation of the MS consists of thousands of XML documents, with a separate file for each individual notebook and a documentary line-by-line encoding of the marks of the page surfaces, including marginal annotations. These can be bundled into larger files, but the major structural divisions in this edition are page surfaces. Chapter, paragraph, and other such meaningful structures were, thankfully for us, encoded carefully in TEI “milestone marker” elements. This means that that meaningful structures in the novel were signaled in position, but not used to provide structure to the digital documents.

The use of “milestone markers” proved to be highly useful in preparing all of the source edition files for comparison with the S-GA files. With careful tracking of all the distinct elements in each edition, we noted where and how the editions marked each meaningful structure in the novel. We applied eXtensible Stylesheets Transformation Language (XSLT) to negotiate the different paradigms of markup in these digital editions. We applied XSLT to “flatten” the structure of all the editions by converting all the meaningful structure elements into “milestone markers”—thinking of them as signal beacons for us in the collation process that would follow. In order to prepare each distinct edition’s files for machine-assisted collation, we studied their structures carefully to identify analogous markup, and we then “flattened” all of the editions to include that meaningful markup. Crucially, we could include only the analogous forms of markup in the collation, and had to screen out other kinds of markup. Markers of volumes, letters, chapters, paragraphs, and poetry were vital points of comparison. However, we also had to exclude—effectively “mask away” from comparison—all of the elements in the S-GA MS files that marked page surfaces and lines on the page. We could not lose these markers: they were important to construct the editions as you see them in the Variorum interface, where we do display lineation for the MS. But we also had to bundle the S-GA page XML files into clusters to align roughly with the structural divisions of the print editions. This stage of work, known as pre-processing required very careful planning.

To guide our work in stages, we followed the Gothenburg Model of computer-aided textual collation, which requires clarity on how we would:

- Tokenize the strings of text to be compared into base units: We would compare words and punctuation, and decide on markup to include as tokens supplying crucial data for comparison;

- Normalize certain literal differences as not meaningful: for example: we must instruct the collation algorithm that “&” is the same as “and”, and also that the

<milestone/>markup in the Shelley-Godwin archive indicating the start of a new paragraph is the same as as start tag for a<p>element in the editions of the print texts. Our list of normalizing algorithims became very extensive over the course of this project. - Align the texts by dividing them into 33 regular portions that share starting and ending points across the five editions. This was complicated by gaps in the manuscript and heavily revised passages and alterations in the chapter divisions in the 1831 text. The alignment challenges with the MS notebooks are explained and visualized later.

- Analyze the output of the machine-assisted collation and look for errors in alignment, normalization, and tokenization to correct.

- Visualize the results of collation, and thereby find bugs to fix or alterations to make in the process.

Alignment proved a significant challenge. We divided the novel into 33 portions (casually deemed “chunks”) that shared the same or very similar passages as starting and ending points. Often these were set at chapter boundaries, or at the start of a passage shared across all five editions, like the famous phrase “It was on a dreary night of November” that was shared in all of the texts. These “chunks” would share much the same end-points as well. These were prepared so that the CollateX collation software would more reliably and efficiently locate variant passages than it could by working with only one long file representing the entire novel for each edition. Aligning the “chunks” that we had for each edition was also important because the manuscript notebooks were not a complete representation of the novel. The MS files do not represent the complete novel as it was later published, so we needed to identify which collation units we had present and where they aligned as precisely as possible with the editions of the published novel.

To understand the contents of the Frankenstein Variorum, it helps to see how the pieces and fragments of the manuscript notebook aligned with the 33 collation units that we prepared for the full print editions available in their totality. The MS notebooks were missing a large portion of the opening of the novel, a full 7 collation units. We found a gap in the middle of the notebook, around which we identified collation unit 19. We also found that the MS notebooks contained a few extra copies of passages at C-20, C-24, and C-29 – C-33. Each of the S-GA MS page files is named to indicate the position of corresponding paper notebook page in one of three boxes at the Bodleian Library, each of which is fully encoded by the Shelley-Godwin Archive. Following the careful work of the S-GA editors in organizing their edition files and encoding helped us immensely in constructing the alignment of the notebooks with the published novel, essential for our collation effort. The following interactive diagram is a visual summary of how the pieces aligned prior to collation:

Preparing a TEI edition

The TEI is the language of the Text Encoding Initiative, an international community that maintains a set of Guidelines that support the preparation of human- and machine-readable texts, optimally in a way that can be shared by scholars and survive changes in publication technologies. In developing this project, our guiding intention was to demonstrate that we could apply the TEI to support the comparison of differently encoded source documents. While many TEI projects prepare “bespoke” or highly customized encoding, that encoding is regularly structured and highly accessible for programmatic mapping from one format to another. We hope that the Frankenstein Variorum provides a good example of how TEI itself can be used to hold data about how distinct digital editions of a work can be compared.

We prepared all editions in XML designed to be compared with one another with computer-aided collation. We planned that our variorum edition files, when complete, would be prepared as TEI documents, and we thought of the TEI encoding language as expressing the meaningful basis for comparison across the differently encoded source editions. But to begin preparing the edition in TEI, we needed to find a way for our differently encoded source texts to share a common language. To begin preparing the edition in TEI, we first converted the old HTML files from the Pennsylvania Electronic edition (PAEE) into simple, clear, and well-formed XML documents using regular expression matching and careful search and replace operations. We also carefully corrected the texts from the 1990s PAEE edition files by consulting print and facsimile editions of the 1818 and 1831 editions.

Elisa Beshero-Bondar prepared a new edition of the Thomas copy marginalia by consulting the source text in person at the Morgan Library & Museum, and reviewing the previous commentary on this material by James Rieger and Nora Crook. She added the Thomas copy marginalia using <add>, <del>, and <note> in the XML of the 1818 edition to represent insertions, deletions, and handwritten notes on the printed text. The 1823 edition was prepared from careful OCR of a photofacsimile thanks to Carnegie Mellon University librarians, and Beshero-Bondar worked with Rikk Mulligan to prepare the XML for the 1823 edition to parallel that of the 1818, Thomas, and 1831 texts. Each of these versions was prepared for collation to share the same XML elements for paragraphs, chapters, letters, lines of poetry, and other structural features as well as inline emphasis of words and phrases in the source documents. Preparing the texts for collation in XML was an early “data output” of our project that we share with the complete Variorum edition as potentially useful to other scholars.

While the simple XML encoding of the 1818, 1823, Thomas, and 1831 editions is designed to be parallel, it is important to point out that we did not change the markup of the manuscript notebooks from the S-GA archive at this stage. We simply bundled each of its separate TEI XML files (one file for each page surface) into larger files to represent Boxes 56 and 57 (containers of the looseleaf sheets remaining of the manuscript notebook. Those boxes are thought to contain a mostly continuous though fragmentary “fair copy” of the manuscript notebook. The “surface and zone” TEI markup of the S-GA MS edition tracked lines of handwritten text on every page surface, including deletions, insertions, and marginal notes. To make it possible to compare the S-GA edition to the others, we first had to establish a method of mapping the S-GA encoding to the simple XML we prepared for the print edition files. As discussed in the previous section, we analyzed the S-GA encoding to map which S-GA TEI elements were equivalent to those in the simple XML we prepared for the print editions, and ensured that the markers of all the structural features (including letters, chapters, and paragraphs) were all signalled with empty milestone markers. Notes to add material in the margins had been encoded at the end of each S-GA page file, so we resequenced these to position them in reading order, following the very clear markup in the S-GA files as to their insertion locations. Much of this resequencing was handled with XSLT to prepare the texts so that marginal additions could be placed in reading sequence. That resequencing was crucial to be able to collate the S-GA TEI with the other documents, because collation proceeds by comparing strings in sequential order.

From Collation Data to Variorum Edition

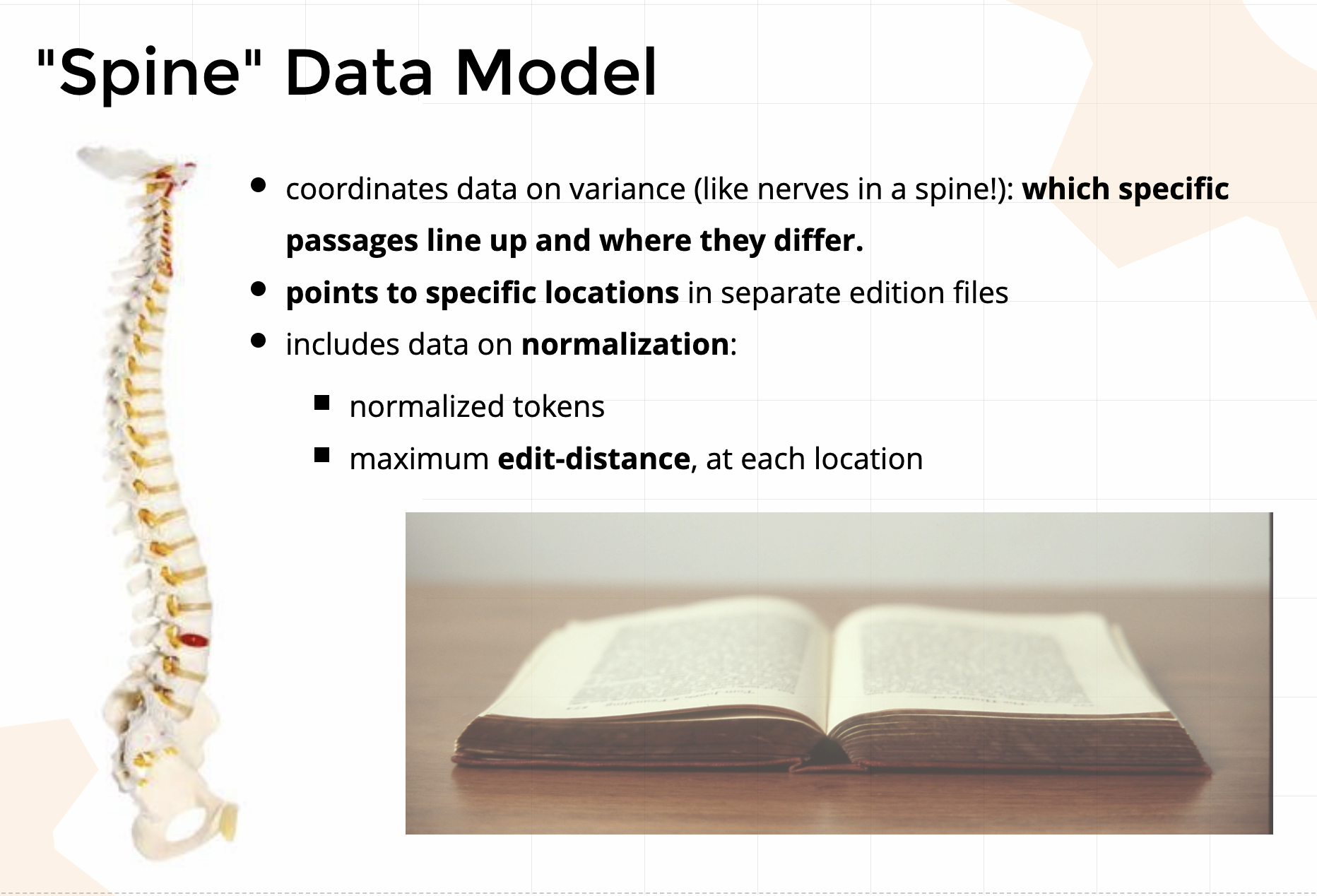

The collation process would read these XML documents we had prepared as long strings of text. It would produce outputs that we could structure to create our Variorum edition. New markup would be added to indicate passages in each document that varied from each of the others. In a way, the markup we prepared was going to be taken apart and reassembed by the collation and the construction of the edition files that we are publishing. To prepare for this process, we transformed the source edition files so that the markup could be radically restructured into to a TEI edition that expresses comparison. The reason why we “flattened” the XML structure of our source edition files and converted their elements into self-closing milestone markers was because the collation process needs to be able to locate alterations that collapse or open up new paragraphs and chapters. We similarly flattened the markup of the Shelley-Godwin archive texts, and we wrote an algorithm in Python to exclude page surface and line markers from the collation, because our process compares what we think of as semantic structures: the paragraphing, the chapter, the volume boundaries. These semantic structures are meaningful for comparison where the page boundaries and lineation do not. When the edition files are thus prepared in comparable “flat” XML, we process them with CollateX, which locates the points of variance (or “deltas”) and outputs these in TEI XML critical apparatus markup. We processed the output of CollateX to create the “spine” of the edition, storing variant information in a TEI critical apparatus. That critical apparatus stores pointers to specific locations in each of the distinct edition files. Designed from the very first output of the collation process, the spine serves as a centralized storage of information about each passage in each of the five texts in the Variorum.

The data stored in the “spine” begins by containing the original text together with its normalized form, organized in units that group variant passages. The spine data serves as a basis for developing the five distinct edition files, through a processing pipeline combining Python and XSLT. For the technical details on how we read and process the collation data from the source texts, calculate edit-distances, and create the editions, see our postcollation pipeline documentation. To summarize the process, it involves:

- Transforming the output of the collation software into a TEI file that stores all information about where all five texts are same and where they are different in the form critical apparatus encoding. This is considered a “standoff” version because it stands alone, outside the five editions, and is designed to link to them and supply information about them.

- Building the edition files from the data stored in the spine. This involves constructing new XML files. Remember how we flattened the XML elements from the source editions to make it possible to compare the markup? Now we have to identify those flattened elements in the text strings, and “raise” them into whole elements again to form their original structures.

- Calculating the extent of variance or edit distance, at each passage that experienced change. Edit distance is a recognizably problematic measure: We can literally calculate the number of characters that make one passage of text different from another, but some changes are obviously more meaningful than others. (For example, in this lightly variant passage, the only difference is punctuation: “away,” vs. “away”, so the edit distance is literally just 1 and the variation is not particularly significant. However, other variant passages might shift meaning by changing just one character: for example, the difference between “newt” and “next” is just one character, as well, though that one character totally changes the meaning of the word and should really be considered more significant a variant. In practice we do see many simple variants indicating tiny changes to syntax or punctuation more like the first example than the second, and we also see very heavily revised longer passages of variance which we really want to stand out and make easy to find. The edit-distance calculation of each edition at a moment of variance is calculated between pairs, each to the others, and we store the maximum edit distance value for use in the edition files in the next step.

- Applying new elements to each edition file to store information about each passage that varies from the other editions. We translate those numbers into four different shades of variation to help make the heavily altered passages easily discoverable, to be displayed as “hotspots” in the edition interface. Where changes to the text involved a shift in paragraph or chapter boundaries, we had to break up a hotspot to fit in pieces around a paragraph ending and beginning so as not to disturb the document structure of the TEI edition files. To enhance the accessibility of the edition to readers who cannot distinguish colors, we made variation based on intensity that can be distinguished in greyscale.

- The spine is finally transformed again, after the edition files are prepared, to set links to each edition file at each locus of variation. After the postCollation pipeline process is complete, the edition data from the spine and edition files is ready to be delivered to the static web interface.

- One last product of the postCollation data processing and the edit-distance calculations is our interactive heatmap for the Variorum that you see on the homepage! This heatmap is directly produced from the data stored in the spine files and expresses that data in scalable vector graphics (SVG), an image format made of XML code and optimal for visualizing data using shapes and intensities of color. The SVG is interactive with links into the Variorum simply because it the spine was designed to store those links. Exposing this heatmapdata from the “spine” also makes it possible to link from one edition directly to each of the others as you are reading a passage in the Variorum Viewer.

The Static Web Interface for the Variorum

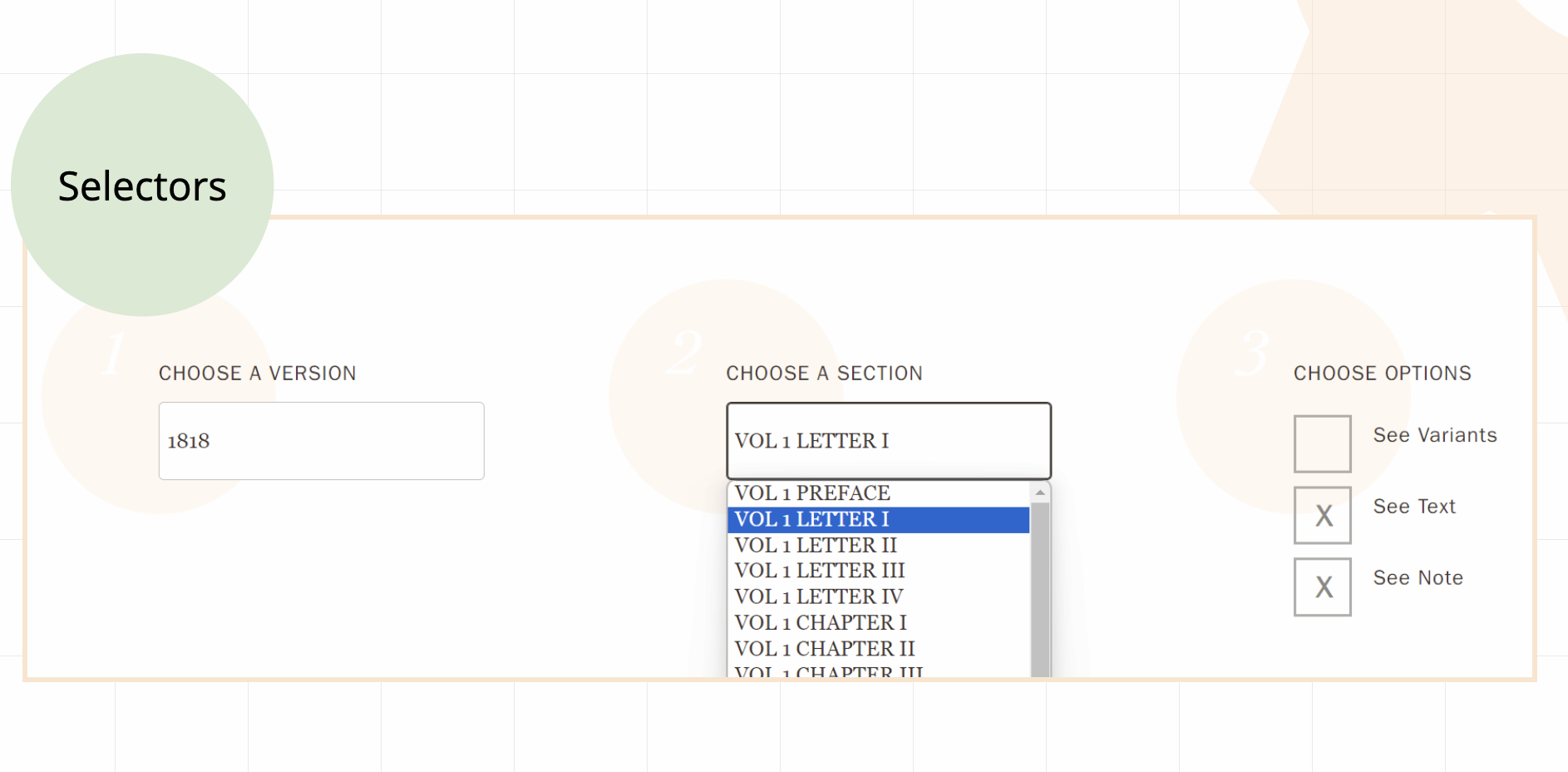

The Frankenstein Variorum Viewer should respond quickly in your web browser, without needing to take time to pull new data from the web when you want to change your view of variant passages or navigate the editions. We designed the edition to be “lightweight” and “speedy” to explore following the principles of minimal computing that keeps its dependencies simple. The Variorum interface relies on its data structure (the “spine”) to deliver options for viewing and navigating entirely in your web browser. It relies on the React and Astro JavaScript web component libraries, designed for optimizing delivery of information rapidly in a static website—a website that does not need to make calls to another computer or database in the network but relies only on your local web browser to deliver the information you request as you explore and select options to view. As you interact with the Variorum Viewer, JavaScript delivers information drawn directly from the edition’s “spine” and makes it possible for you to rapidly navigate the site. For those seeking more information about these technologies, here is a good set of orientation materials curated by New York University Libraries on static websites an minimal computing. The interface of the Frankenstein Variorum was originally designed in React by the Agile Project Development team back in 2018. From 2023-2024, Yuying Jin worked with guidance from Raffaele Viglianti on migrating the technology to React and Astro libraries to work more closely with the TEI spine data and edition files.

Astro is a static website generator for which Raffaele Viglianti developed a special TEI package, related to CETEIcean, a Javascript library that renders TEI XML directly in the browser. When you select a button or menu bar on the site, Astro coordinates and delivers views from a total of 146 chapter files (the total of all chapter files across all five versions of Frankenstein. It works together with React, which supports selector menus and interactive hotspots and displays the variants in the sidebar.

Technologies used in the project

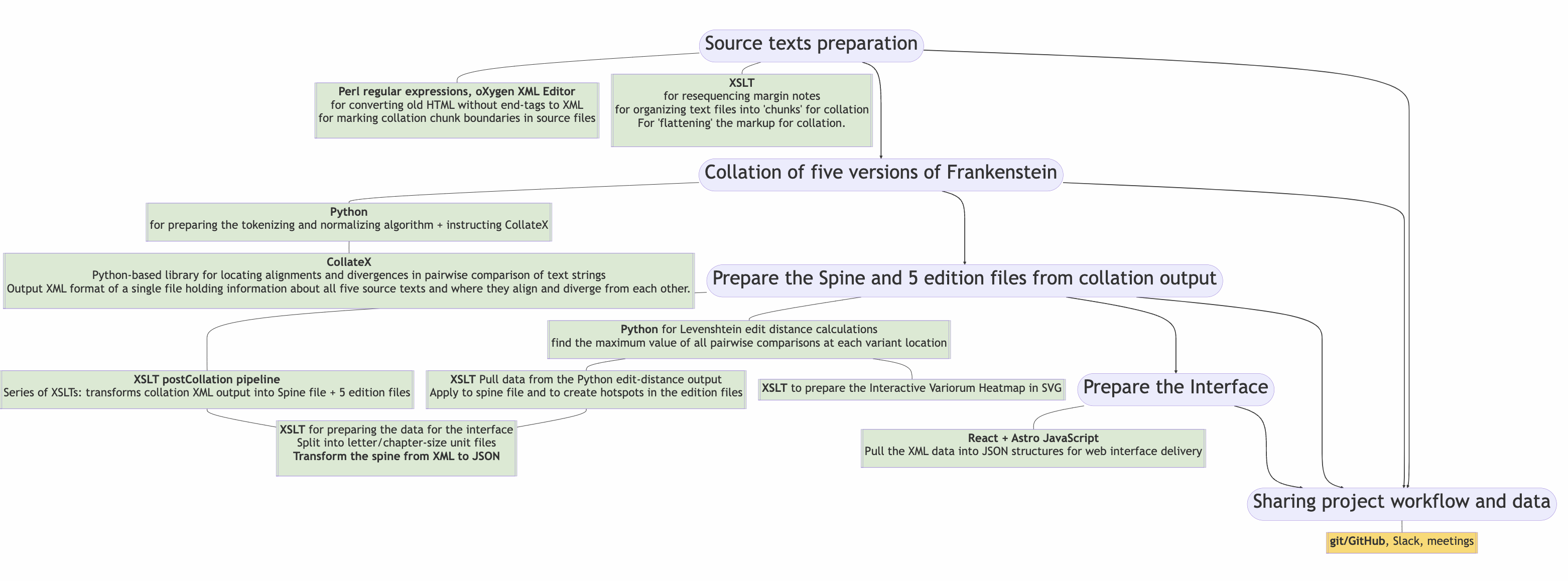

Each stage of this project depended on its own collection of technologies and challenges. Our work was a combination of XML stack technologies (XML and XSLT), combined with Python for handling documents and markup as strings with regular expressions, and finally JavaScript libraries React and Astro with git/GitHub to package our data into web components in a static website. Here is a visual summary of them all!

Selection of presentations and papers

Over the years while we were in various stages of heated development on this project, we delievered lots of conference presentations and invited talks and related publications. Here is a selection in chronological order from 2018 to the present.

-

The Pittsburgh Digital Frankenstein Project: Reassembling Textual Bodies: Presentation for the Humanities Center at the University of Pittsburgh, Cathedral of Learning on 2 April 2018. Explanation of the project and range of collaborating people and institutions. Updated with material on latest full collation of manuscript notebooks, Thomas edition, and 1818, 1823, and 1831 published editions.

-

Bicentennial Bits and Bytes: The Pittsburgh Digital Frankenstein Project: MLA 2018 panel presentation on our variorum edition project, reconciling previous digital editions, ongoing stylometric research, and annotation development.

-

Frankenstein and Text Genetics: an introduction to the novel and its contexts, and our project’s connection with the Shelley-Godwin Archive

-

a slide presentation by Elisa Beshero-Bondar and Raffaele Viglianti for the 2017 NASSR Conference on 11 August 2017: http://bit.ly/NASSR_BicFrank

-

Balisage Proceedings for the Symposium on Up-Conversion and Up-Translation (31 July 2017): Rebuilding a digital Frankenstein by 2018: Towards a theory of losses and gains in up-translation

- In developing the postCollation pipeline, we needed to find out how to “raise” XML elements that we had flattened to be read as text strings in the collation process. This presentation is all about methods that can work and we learned from this how to build our postCollation pipeline: Flattening and unflattening XML markup: a Zen garden of “raising” methods (slide presentation at Balisage 2018)

- Published paper: Birnbaum, David J., Elisa E. Beshero-Bondar and C. M. Sperberg-McQueen. “Flattening and unflattening XML markup: a Zen garden of XSLT and other tools.” Balisage Series on Markup Technologies, vol. 21 (2018). https://doi.org/10.4242/BalisageVol21.Birnbaum01.

-

The Frankenstein Variorum Challenge: Finding a Clearer View of Change Over Time is a slide presentation given by Elisa Beshero-Bondar and Rikk Mulligan on July 12, 2019 at the Digital Humanities Conference in Utrecht, Netherlands.

- Adventures in Correcting XML Collation Problems with Python and XSLT: Untangling the Frankenstein Variorum (slide presentation at Balisage 2022).

- Published paper: Beshero-Bondar, Elisa E. “Adventures in Correcting XML Collation Problems with Python and XSLT: Untangling the Frankenstein Variorum.” Presented at Balisage: The Markup Conference 2022, Washington, DC, August 1 - 5, 2022. Balisage Series on Markup Technologies, vol. 27 (2022). https://doi.org/10.4242/BalisageVol27.Beshero-Bondar01.

- On the development of the TEI for the edition and spine: Between bespoke customization and expressive interface: A reflection from the Frankenstein Variorum by Elisa Beshero-Bondar, Raffaele Viglianti, and Yuying Jin for TEI-MEC Conference, September 2023 in Paderborn, Germany.

- Reconciliation and Interchange: Collating the Text as Page in the Frankenstein Variorum presentation by Elisa Beshero-Bondar for the Editing the Text, Editing the Page Conference conference at the University of Venice, 6 October 2023.

- On the completion of the complete Frankenstein Variorum: A Complete Frankenstein Variorum: Bridging digital resources and sharing the theory of edition presentation by Elisa Beshero-Bondar, Raffaele Viglianti, and Yuying Jin at DH 2024: Reinvention & Responsibility, George Mason University, Washington, DC, 8 August 2024.

- Celebrating the official launch of the Frankenstein Variorum with the Romanticist community: Introducing the Complete Frankenstein Variorum: Navigating Five Versions of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, by Elisa Beshero-Bondar at NASSR 2024, Washington, DC, 17 August 2024.